New Museum Triennial

Are the Curators the Saboteurs?

During the New Museum Triennial opening night - I - along with many other eager art world insiders, furtively read the wall text of its highly anticipated Triennial, “Songs for Sabotage". After the first few sentences, the grouping looked up, and gave a serious pause of befuddlement. We looked toward our respective exhibition buddies as a kind of self-conscious intellectual “check” at our severe disbelief of the curators' chosen word “propaganda” to characterize the artists' activism. It was a collective response – not to be minimized - as one similar to a crowd’s gasp whilst watching a fallen Olympian.

It stated:

Together, the artists in “Songs for Sabotage” propose a kind of propaganda, engaging with new and traditional media in order to reveal the built systems that construct our reality, images, and truths. The exhibition amounts to a call for action, an active engagement, and an interference in political and social structures…

The word “propaganda” was not only a surprise to most of us - it created what I recognized as a reaction of disdain.

I was, to be blunt, extremely disappointed by this curatorial statement. I thought, as an art historical product of post-structuralism theory, that such overly moralistic curatorial proclamations reductively conflate the maker’s purpose with a singular outcome or interpretation were practices long in our past. I wondered if such statements perhaps both reveal excessively simplistic generalizations and belie a pedagogically naiveté of a new generation of curators. I am not disputing, nor contesting, that there is a vivacious and renewed interest in activist art amongst a new generation of global artists. If anything, as someone who has celebrated authenticity of the 70's and 80's activist idealism, the exhibition signals a moment of return which I welcome in its strive for change through expressions of authenticity. But, by labeling the artists’ aesthetic practice with the word “propaganda,” a word which advocates the use of oppressive forces, totalitarian regimes and disingenuous intent, the curators’ notion appears completely contrary to the agenda of the artists. Furthermore, this curatorial premise undoes its own purpose and is completely contrary to its proffering: diversity and complexity of the artists; the multiplicity of art forms and expressions; and the viewers’ consequent variety and freedom of interpretation. Quite simply, in my view, this curatorial framework is painfully reductive and problematic to the viewers’ experience of the selected works.

Coming from the generation of art historians and thinkers born into structuralism established by those such as Roland Bartes, I take as a given that professional curatorial practice begins with the starting point of authorship “as an open text” simultaneously subject to the multiplicity of “meanings” of the reader. Since the 1970's, Reception Theory & Aesthetics (Rezeptionsästhetik), art historian’s theoretical heritage from German literary theorists, most notably Hans Robert Jauss, acknowledge each individual viewer’s subjective power in the process of interpretation. Thus, the meaning of a work of art cannot be “directed” by the maker, and even with a fixed intent of the creator, its value is intimately reliant on its relationship of the viewer.

Surprisingly, the wall text, here and throughout the show, refused to acknowledge the gap between the artists’ “intent” versus the viewers’ “reception” of meaning. I was a bit incredulous of the possibility that the new generation of artists would display such hubris and lack self-awareness in proposing that their intent to control interpretation is undeniably associated with the action and agenda of propaganda. Upon reflection, however, perhaps its merely the curatorial framework which requires some academic reflexivity and self-awareness. It seems the show calls for an alignment between artists and curators purposes, as well as aesthetic contextualization. The show, as it reveals itself through the artists’ pieces, suggests their sincerity and concern for society and thus their aesthetic practices are largely focused on issues of inclusivity politics, subjectivity, fluidity of identity, individualism, and multiplicity.

As a young professional, I was actively associated with the New Museum during the late 1980's under my heroine, Marcia Tucker, and her legendary leadership. I wonder what she would have thought of the use of propaganda to describe a young artists, replete with an idealism to create change through art. It should be noted that many of the artists are not merely repeating the didacticism associated with 1980's culture wars, when artists rebelled against the homogeneity and generalizations of expressions and interpretations. But certainly, what the New Museum artists are seeking should be contextualized to these 1980's art activists, who celebrated the individuality and the subjectivity of the reader (and subsequent generations of curators equally embraced such). This historical lineage of activist art, however, held a very different agenda to that of directive control suggested in this show by the curators. Such predecessors sought to open dialogues and perceptions by debunking stereotypes, celebrating subcultures, and affirming difference. What would Tucker make of such a forthright and singular pronouncement by a group of artists who are immensely diverse, both geopolitically as well in expression of form. Are the curators the real saboteurs of this show?

Perhaps the curators identifying such strategies as “models” was their intention to suggest diversity – but nevertheless the simplicity of “intent = meaning” is a very misplaced formula, one which is theoretically problematic. Given that so many viewers depend on wall text to engage with these types of dialogues, often overwhelming or inaccessible to the masses, I harbored the hope that the curators were more nuanced, responsible and less directive in their use of language. Given the strength of much of the work, it was disconcerting that viewer’s “understanding” or “viewpoints” were so soiled by the opening wall text. In short, a better curatorial framework would have been more honorable to the work and the artists’ agenda. I regret I did not get a chance to speak to any of the artists but given the power of the New Museum in the art world, I doubt that many would express disdain for their current contextualization, no matter how unfitting it might be.

However, one must sidestep the curatorial premise and theoretical context, even if it provided an unnecessary distraction to the strength of many of the individual works and commonalities of a generation of artists. A summary of a few important thematic commonalities running through the show, perhaps tritely identified as “trends” or “takeaways” that reflect current curatorial notions of what constitutes “good" art now, are salient to highlight:

1| Many of the works exhibit a strong emphasis on craft – not just in materials – but also the attention to manipulating materials in a highly laborious manner.

2| The art world, I think, would finally agree that the evolution of craft as fine art is complete, and curators certainly no longer denigrate this as women’s labor or secondary to fine art. That’s all good with me to see the total collapse of any hierarchy of materials.

3| The didactic is now cool again. In the 1980’s didacticism in activist art was seen as disruptive. But the following generation of artists from 1990's and 2000's, most notably in the West, were highly discouraged with “don’t be didactic” as a rule by their studio advisors (as I recall many artists friends telling me). Clearly, that moment is over.

4| There is a renewed and unabashed interest in the ceremonious.

5| Unfortunately, curatorial selection in the area of new media is still sadly lacking. The show did not present a more expansive perspective on new media and the works included were devoid of any development from early video art wherein ideology is sophomorically prioritized over form and therefore poses as rigorous conceptualism. So, ideas trump form and aesthetics. In today's cultural climate, it’s not even remotely reflective of our highly sophisticated vernacular culture of new media and should capture the richness of a generation of creatives native to such. This is particularly disappointing given Rhizome, an incredibly vibrant archive and scholarly initiative, is housed in the New Museum lab. Simply, they could and should have done much better with both the selection of works, even if several were effectively produced or installed.

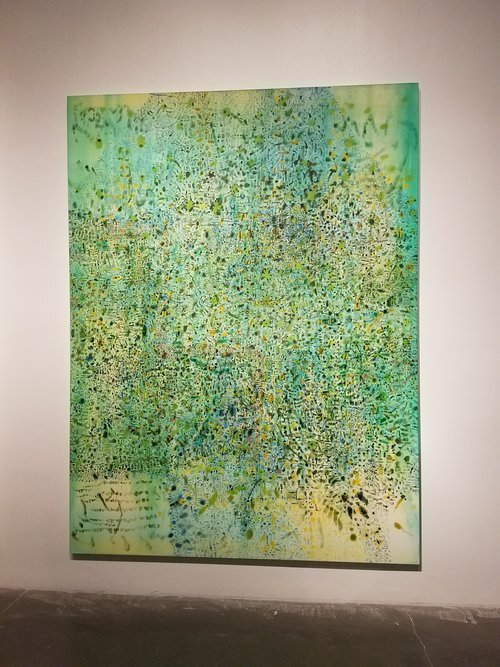

6| admittedly not a new artistic interest, but rather a continuation of artists' celebration of color - Representation characterized with vibrant palettes is no longer an aesthetic associated with the decorative and, therefore, reflects a freedom from the hegemony of Western modernism's color chart. Color is wanton in its ability to occupy the realm of the serious and political. Sometimes, however, and this is a generalization of many artists working now, their aesthetic choices come to present themselves as somewhat shallow stabs at bourgeois taste, gratuitous in their gestures, given we know artists, such as Stella since the 1980's, have tackled color as bad taste for decades.

All in all, with some curatorial misgivings, the show’s lack of self-awareness and mediocre installation itself, which admittedly is not an easy task, there were many works that are exceedingly strong in their variety of styles, expressions and forms. Thus, I think many of the works in themselves exhibited clever selection, which is of credit to the curators.

Some of the notable highlights are shown here: